Until you’re a fan of darkish or shady patterns, you most likely battle sometimes with integrity in your design observe: balancing stakeholder needs in opposition to person wants, for instance, or guiding customers to hero paths whereas additionally granting them freedom to discover.

Article Continues Under

Lately, I labored on redesigning a cellular timebanking app, which helps neighbors share providers and construct supportive relationships. The general public-good side of the mission was interesting; the app’s values of group, belief, and help saved us targeted on assembly customers’ wants and being sincere in our design. So in fact we wished to point out customers solely info that was actually, concretely true. However what if a slight deviation from the reality would make customers happier and extra environment friendly in attaining their objectives? What if fudging an interface helped reassure and velocity the person alongside her means?

This isn’t an unusual challenge. You’ve most likely run into “Shut Door” buttons that don’t actually shut the elevator, or sneaky progress bars that fill at an arbitrary price—these false affordances and placebo buttons are in all places, and would possibly make life appear a bit simpler. However is that this moral design? And may we construct a framework for working with false affordances and designing with integrity?

What’s the hubbub?#section2

Timebanks are native, digital exchanges during which neighbors can put up requests for and gives of service in trade for “timedollars,” a non-fungible different forex primarily based on an hour of service. For instance, if I do an hour of stitching for you, I can flip round and “spend” that one timedollar I earned on having somebody mow my garden for an hour. Granted, I can’t sew and don’t have a garden, however you get the concept.

By enabling neighbors to attach and assist one another, timebanks create group in what was simply a location. By way of cellular timebanking, folks really feel extra linked with their neighbors and supported of their every day lives—in actual fact, that’s the worth proposition that guided our mission.

With groups recruited from PARC, Pennsylvania State College, and Carnegie Mellon College, our purpose was to revamp the prevailing timebanking cellular app to be extra usable and to attach customers extra simply by way of context-aware and matching applied sciences.

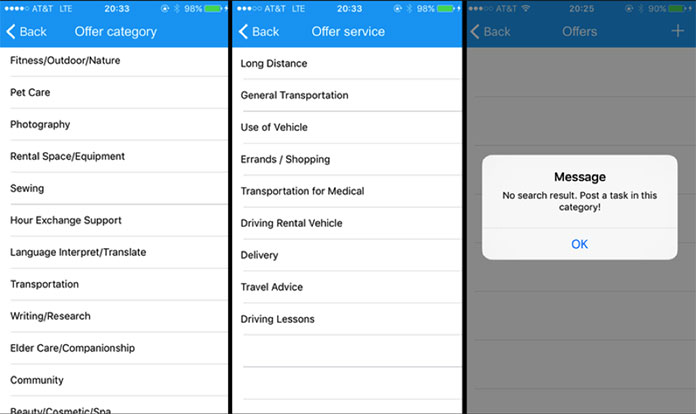

We began by evaluating points with the prevailing app (mapping the IA, noting lifeless ends and redundancies, auditing the content material) and analyzing the info on person actions that appeared most problematic. As an example, gives and requests for timebanking providers had been, within the current app, positioned in multilevel, hierarchical class lists—like Craigslist, however many layers deep.

Our analyses confirmed us two fascinating issues: first, that the service requested most frequently was a experience (similar to to the physician or for groceries; the person inhabitants was typically older and fewer bodily cellular); and second, that many postings by customers to supply or request rides had been deserted in some unspecified time in the future within the course of.

We speculated that maybe the well timed nature of experience wants discouraged customers from posting a request to a static checklist; maybe drivers wouldn’t consider diving down right into a static checklist to say, “Hey, I commute from close to X to Y at about this time a couple of days per week—want a carry?” So we integrated walk-throughs of the outdated app into semi-structured interviews we had been already conducting in our analysis on peer-to-peer sharing motivations; contributors’ actions and responses supported our speculations.

With that in thoughts, we proposed and began prototyping a brand new characteristic, TransportShare, on the high stage of the app. We hoped that its presence on the app’s residence display would encourage use, and its similarity to in style ride-requesting apps would ease customers into the expertise.

We created an inventory of parameters the person must specify: beginning/pickup level, ending/drop-off level, pickup time, “fudge issue” (how versatile this time is), one-way/roundtrip, and a textual content subject for any particular wants or issues. Then we constructed prototypes, transferring from sketches to low-fidelity mockups to higher-fidelity, interactive prototypes utilizing Sketch and Invision.

The alternatives we make#section3

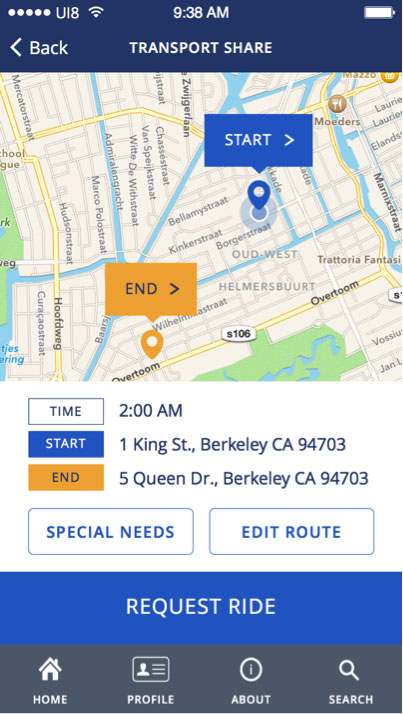

Our moral dilemma emerged as we designed the ride-request course of. After the person specifies “Begin” and “Finish” factors for a experience, the app exhibits a abstract display with these factors, the time of the experience, and some choices.

Because you’re all crackerjack designers, you’ve seen that there is no such thing as a line connecting the Begin and Finish factors, the best way there’s in different apps that plot a route, similar to Google or Apple Maps. This was intentional. Our person analysis confirmed that folks providing rides had been typically operating different errands or might have to make detours. Since we couldn’t anticipate these wants, we couldn’t assure a selected route; displaying a route could be, to some excessive diploma of chance, improper. And—notably in an app that hinged on group values and honesty—that felt misleading.

Being truthful to the nth diploma is the moral selection, proper? We wouldn’t wish to show something that may not be one hundred pc correct and deceive the person, proper? Doing so could be unhealthy, proper? Proper?

Oh, I used to be improper. So, so improper.

And lo, got here…a check#section4

At this level, we had strong analysis questions we wouldn’t have had at an earlier stage and clear, clickable prototypes in Invision we might current to contributors. With no price range for testing, I discovered potential contributors at a Meetup designed to let folks share and check their tasks and chosen those who had used some type of peer-to-peer app. (We’re planning subsequent usability exams with extra senior contributors, particularly for readability and accessibility.)

I performed the exams with one person at a time, first briefing them on the character of timebanks (you’ve lived by way of that already), and setting the state of affairs that they’re in want of a neighbor to drive them to a close-by location. They got latitude in selecting if this may be a experience for now or later, and one-way or roundtrip. Pondering out loud was inspired, in fact.

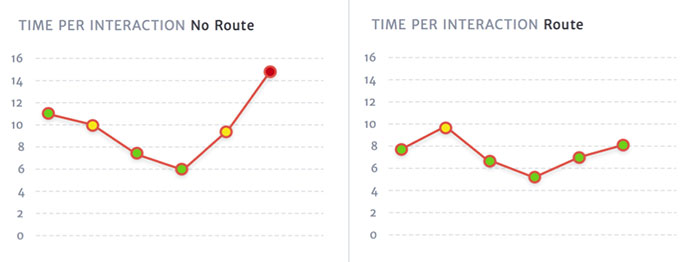

As they stepped by way of the duty, I measured each the time spent per display (or subtask) and the emotional response (gauged by facial features and tone of responses).

| Subtask | Common | Outlier | Emotion |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1: Set request time | 11s | 12s | |

| 2: Set one-way/round-trip | 10s | 17s | |

| 3: Choose begin | 7.5s | 11s | |

| 4: Choose vacation spot | 6s | 8s | |

| 5: Affirm request | 9.5s | 14s | |

| 6: Evaluation request | 14.8s | 18s |

The customers tended to maneuver simply by way of your complete process till they hit Subtask 6 (reviewing the request on the abstract display), and I noticed there was an issue.

Members visibly hesitated; they mentioned issues like “ummm…”; their fingers and eyes traced backwards and forwards over the map, roughly between the tagged Begin and Finish factors. Once I requested open-ended questions similar to, “What are you seeing?” and “What did you count on to see?” the contributors mentioned they had been anticipating to see route traces between the Begin and the Finish.

In debrief classes, contributors mentioned they knew that any route they could have seen on the abstract display wouldn’t be the “actual” route, that drivers might take totally different paths at their very own discretion. However the lack of traces connecting the Begin and Finish factors disconcerted them and brought on hesitation and unease.

Customers had been accustomed to seeing traces connecting the top factors of their journey. I might see this within the time it took them to work together with that display, of their faces, and of their think-alouds. Some thought they couldn’t full the duty or that the app wasn’t completed with its job; others reported a decrease stage of belief within the app. We’d made an assumption—grounded in honesty—about what customers wished to see, and found that it didn’t work for them.

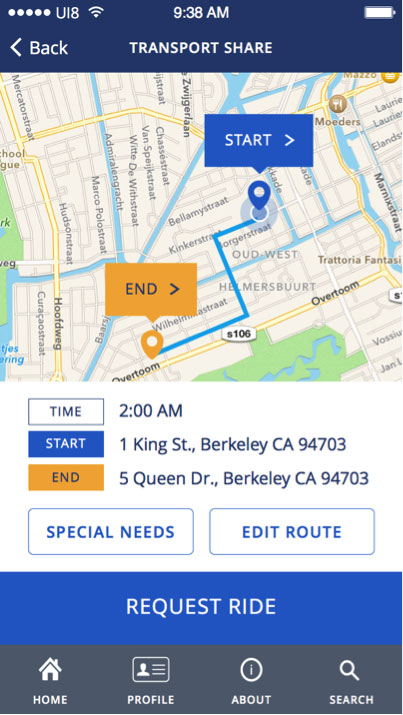

With these ends in thoughts, I made a decision to run a smaller usability check with the identical protocol and screens, with one change: a line connecting the Begin and Finish factors.

This time, the contributors mentioned they knew the drivers may not take that route, nevertheless it didn’t matter—route traces had been what they anticipated to see. (Maybe this is a sign they could not belief Google or Apple Maps pathfinding, however we’re not at that stage of cynicism, not but.)

| Subtask | Common | Outlier | Emotion |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1: Set request time | 7.8s | 13s | |

| 2: Set one-way/roundtrip | 9.8s | 11s | |

| 3: Choose begin | 6.5s | 8s | |

| 4: Choose vacation spot | 5.3 | 6s | |

| 5: Affirm request | 6.8s | 8s | |

| 6: Evaluation request | 8s | 9s |

I graphed out the common person time per display and averaged emotional response (noticed: constructive, unfavourable, meh). I feel it’s not unreasonable to see low time per interplay plus constructive emotion as a superb signal, whereas excessive time per interplay plus unfavourable emotion as an indication that I wanted to return and have a look at an issue.

The distinction is only a line—a line contributors are both explicitly or implicitly conscious isn’t a real illustration of actuality. However the contributors discovered the road comforting, to the purpose the place, with out it, usability took a critical hit.

So once you get in an elevator, do you press the “Shut Door” button? In that case, what prompted you? Did you press it as soon as and wait, or maintain urgent till the door truly closed? How did that make you’re feeling, the urgent, and even simply the existence, of mentioned button?

After all, we now know that the “Shut Door” button does precisely nothing. It’s a false affordance, or placebo button.

Which brings us again to the moral query. Ought to I design in parts that don’t technically mislead, however reassure and enhance consolation and effectiveness of the product for the person? Does intention forestall this from being a darkish sample?

Bear in mind, darkish patterns are darkish not as a result of they aren’t efficient—they’re very efficient—however as a result of they put the person in positions of appearing in opposition to their very own pursuits. Kim Goodwin speaks of well-designed providers and merchandise appearing as thoughtful people ought to act; maybe generally a thoughtful human tells white lies (I’m not judging your relationships, by the best way). However then once more, generally white lies are a seed that turns into an intractable drawback or a nasty behavior. Is there a approach to construct a framework in order that we will decide when such a design determination is moral, as a substitute of simply efficient?

I initially wrote about this solely to ask a query and open a dialog. In consequence, the heuristics under are within the early phases. I welcome suggestions and dialogue.

- Match between affordance and actual world. The affordance (false or placebo) ought to relate on to the scenario the person is in, quite than lead the person away to a brand new context.

- Present constructive emotional worth. The designed affordance ought to reassure and enhance consolation, not create anxiousness. Lulling right into a stupor goes too far, although.

- Present reduction from anxiousness or rigidity. If the product can’t present constructive emotional worth, the affordance ought to serve to scale back or resolve any extra anxiousness.

- Improve the person’s effectiveness. The affordance ought to assist enhance effectivity by decreasing steps, distractions, and confusion.

- Present actionable intelligence. The affordance ought to assist the person know what’s going on and the place to go subsequent.

- Add context. The affordance ought to supply extra sign, not introduce noise.

- Transfer the person towards their desired consequence. The affordance ought to assist the person make an knowledgeable determination, course of knowledge, or in any other case proceed in the direction of their purpose. Notice that enterprise objectives are usually not the identical as person objectives.

- Resolve potential battle. An affordance ought to assist the person determine between decisions that may in any other case be complicated or deceptive.

These are usually not mutually unique, nor are they a guidelines. Checking off your complete checklist received’t assure that your whole moral obligations are met, however I hope that assembly most or all of them will weed out design that lacks integrity.

One unresolved query I’d like to lift for debate is the illustration of the false affordance or placebo. The “Shut Door” button wouldn’t work if labeled “This Doesn’t Shut the Door however Press it Anyway,” however in my case we do wish to make the person conscious that the route line shouldn’t be the route the experience will essentially take. The best way to stability this? When does it turn into deception?

As well as, I can suggest Dan Lockton’s Design with Intent toolkit, licensed below the Inventive Commons 3.0 customary. And Cennydd Bowles has written and spoken on the bigger problems with moral design; if this can be a subject of curiosity (and certainly, you’ve learn many phrases on the subject to get thus far), it’s value diving into his web site.

I hope to maintain excited about and refining these heuristics with extra suggestions from designers such as you. Collectively, let’s construct instruments to assist us design with integrity.